Tim Chapman in the Spotlight

How Can You Write What You Know If You Don’t Know Anything?

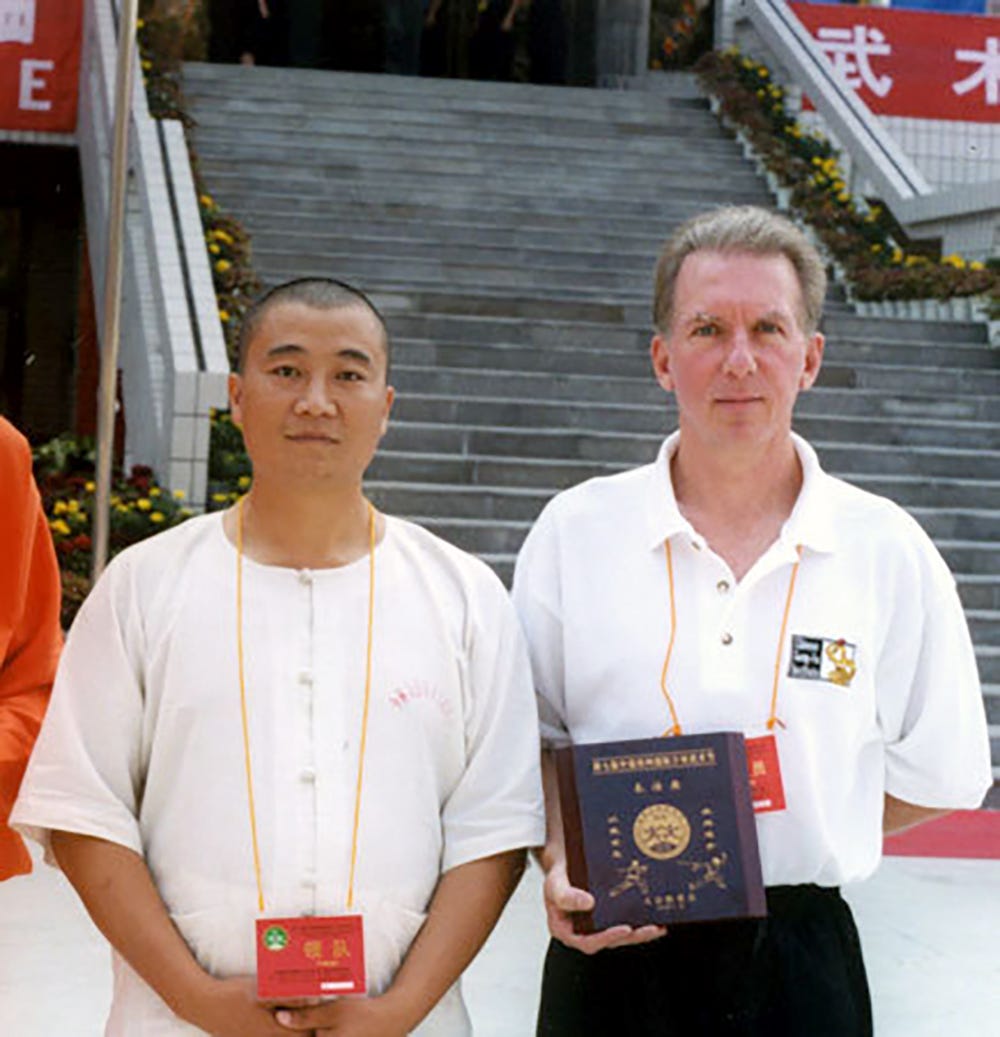

There’s an old saying that experience is the best teacher. There are experiences that we seek out and experiences that are foisted on us by circumstance. In either case, to learn from the experience, you have to be receptive to the teaching. I’ve spent a lot of time inviting experience into my life. I’ve lived in a gorgeous Hollywood Hills bungalow and in a condemned apartment building where I had to put the legs of my bed into cans of alcohol at night to keep the roaches from climbing into bed with me. I lived in a van (not down by the river), and I lived on a boat. I’ve practiced martial arts with a Shaolin monk in China and camped on beaches in Central America. I’ve had relationships that were fulfilling and a few that were toxic. After I got through bumming around the west coast, I earned a couple of college degrees to prepare for the more than sixty jobs I’ve had before turning to writing. Most of the jobs were short term—I only lasted four hours flipping burgers at McDonalds before getting into a fistfight with the assistant manager. My longest and most fulfilling job was a ten-year stint teaching writing at an inner-city college.

I’ve been a cab driver, a garbage man, and a forensic scientist with the Chicago Police Department. All of this has molded my world view, my personality, and my writing. As long as my memory holds out, I have access to a wealth of characters and situations to use in my stories. One job that’s come in handy for writing crime stories was working as an operative for West Coast Detectives.

When I was a kid, I was a voracious (flashlight under the covers) reader, and by far, my favorite books were detective novels. I wasn’t interested in police procedurals or whodunnits. The guys I liked lived in a gritty world where they had to bend the rules to protect the innocent and bring about their own brand of justice.

Travis McGee, Sam Spade, the Continental Op, and Phillip Marlow each had their own code of conduct. To quote Sam Spade from The Maltese Falcon, “Don’t be too sure I’m as crooked as I’m supposed to be. That kind of reputation might be good business – bringing in high-priced jobs and making it easier to deal with the enemy.”

Around 1980, I was living in an apartment in North Hollywood, painting pictures to sell at art shows, taking martial arts lessons from Frank Dux (the Bloodsport guy), and doing odd jobs like pushing a food cart at the Wild West Days festival. The owner of the cart had me dress up like a cowboy to sell quiche to the fans of country rock music. Quiche, by the way, was not a popular food item for that venue. One day, I saw an employment ad in the newspaper for the West Coast Detective Agency. I decided to find out what being a real detective was like. The guy who trained me, let’s call him Rusty, was a stocky cigarette-smoking ex-cop with sweat stains under his arms and a “unique” sense of humor. He decided that, before giving me an assignment, I needed to learn to shoot, so he sent me to a local range for a pistol course. Then he took me up into the hills east of Burbank for a shotgun lesson.

It was a typically hot day in the valley, and the inside of Rusty’s sedan smelled like stale tobacco and lunch meat. Having the windows open barely diluted the odors. Rusty drove like a cop—running stop signs, tailgating, and speeding around tight curves. By the time he skidded to a stop in the dusty tree-rimmed grove where he staged target practice for newbies, we were both sweaty, and I was a little nauseated. Rusty handed me a cardboard box filled with empty bottles and took a pump action shotgun and a box of shells from the car’s trunk. He tossed me the shotgun and walked about thirty feet toward the trees to set up a couple of the bottles, then came back, took the gun, and loaded the shells.

“Ever shoot one of these?” he asked.

I said that I hadn’t, and he responded with an enigmatic grin. I learned what that meant a few minutes later.

“So imagine those bottles are some dirtbag’s legs. You don’t want to kill him; you want to blow his legs out from under him, but you’ve got to compensate for the barrel kicking up, so aim at the ground in front of the bottles.”

I snugged the butt up against my shoulder, pumped a round into the chamber, and pulled the trigger. Suddenly I was lying on the ground, and Rusty was laughing so hard he had a coughing fit. Still chuckling, he said, “I’m sorry, kid. I couldn’t resist. That first shell was a magnum load. Get up and try again. I promise the others are just bird shot.”

Rusty offered me five assignments during the short time I worked for him. Being a strong believer in collective bargaining, and having a date with the agency’s sultry- voiced dispatcher, I turned down the assignment of sitting on a Burbank production company’s roof with a rifle to intimidate the strikers marching below. But let me tell you about the assignment that gave me fodder for the story, Handy Man, that I wrote for the March/April 2018 issue of “Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine.”

There used to be a chain of stores called Tower Records that carried vinyl records, cassette music tapes, and VHS video tapes. The location near UCLA in Westwood Village was large, and busy, and had a shrinkage problem. The chain hired West Coast Detectives to do undercover surveillance. The store manager told us there was rampant shoplifting, and he wanted the thieves caught and prosecuted—no one getting off with a warning. I was on the day shift, and another guy was on evenings.

The manager opened the store, went home early for lunch, and came back to work for a couple hours in the evening and lock up. I worked plainclothes, and in addition to mingling with the customers while pretending to shop, I had a one-way mirror in an alcove next to the upstairs office and break room that gave me a good view of the sales floor.

During my first week there, I discouraged more shoplifters than I caught. The alcove was hot (and had a smell I suspected was a combination of the cologne and BO of the other operative), so I preferred spending my time on the floor. There were a couple of large convex mirrors at the ends of the aisles, so it was easy to catch college students stashing tapes when the store wasn’t busy. Letting a kid know I knew what he’d stuffed down his pants and escorting him to the register to pay for it worked out okay for both of us. I took the few shoplifters I grabbed as they were stepping onto the sidewalk up to the break room and explained what their futures would be like if I called the police. Then I called their mother or father to pick them up. One high school kid’s father started beating him in front of me, and I had to explain what his future would be like if I called the cops on him. It looked like he was going to start in on me until I picked up the phone. I thought I’d helped the kid out, but as he and his dad left the store he turned to give me the finger and shout, “Fuck you, hippie!”

I only caught a few thieves while looking down on the sales floor from the alcove. The one who left the biggest impression was a middle-aged man in an expensive-looking suit. He carried a stack of record albums to a far corner, out of view of the aisle mirrors. Then he set his briefcase on the stacks, opened it, and started shoveling in the records. I ran down the stairs and caught him just as he was leaving the store.

I came up behind him and said, “Excuse me, sir. Can I take a look at your briefcase?” He turned around and looked down at the case in his hand, then lifted it just enough for me to grab it. I put my other hand on his arm. “Let’s go back inside, shall we?”

I expected him to pull his arm away and run off. He didn’t. His shoulders slumped, and he let out a sigh and followed me in and up to the break room. I had wanted to call the cops on this guy. He was a full-grown adult and I was just a twenty-something artist trying to be a tough guy and ignore my imposter syndrome. I figured I had something to prove. But the power dynamic had shifted. He started crying in the break room, snuffling and blowing his nose.

“Look,” he said, “I’ve got a family. If I’m arrested, I’ll lose my job. Please don’t…”

“What do you do?”

“I’m, I’m a lawyer. I’ll be disbarred. Come on, man. I’ve got kids.”

So, I let him go too.

“Leave the briefcase,” I said, “and get some help.”

At the end of my second week at Tower, Rusty called and told me to come into the office. The manager had complained that I was letting everyone go when he had specified a no-tolerance policy. “I get it, kid. You wanna be a nice guy, but we’re not in the nice guy business. I’d transfer you, but I don’t have another open assignment right now, and I don’t have another operative to put in at Tower. Get your shit together, or you’ll lose us this account. That would make me unhappy. Understand?”

I said I understood.

The next day the Tower Records manager confronted me right before he went home for lunch.

“Your boss said he straightened you out. No more bullshit. No more catch and release. Understand?”

Again, I said I understood.

Two days later, I got a call from the agency dispatcher. I hadn’t called her after our date, and she sounded a little, um, brusque on the phone. “Rusty says not to go to work today. The Tower job is finished. Come to the office tomorrow. He’s got a new assignment for you.” Click.

Rusty did give me a new assignment, and he told me why the Tower Records assignment was over. It had nothing to do with me.

“It was an inside job,” Rusty said. “The manager was a dirtbag. See, every night when he closed the store he was supposed to phone the alarm company. He and the rest of the staff would then have three minutes to exit the store and lock the doors before the alarms were activated. This guy would gather all the employees at the front door, call the alarm company from the phone by the cash registers, and march everyone out to watch him lock the doors. On the nights he stole merchandise he’d call his girlfriend, pretending it was the alarm company, drive around until everyone was gone, then come back to load up his trunk with merchandise. Then he’d call the real alarm company, lock up and go home. He exaggerated the shoplifting problem to cover his stealing.”

“How’d you catch him?” I asked.

“Your nighttime counterpart went across the street for some take out chicken or something after his shift and saw the guy loading up his trunk.”

That job, and my time working as a forensic scientist, have given me plenty of source material for my crime stories, but it hasn’t been the events as much as the people I’ve met that have proved valuable. The point of this post (yes, please, get to the point) isn’t that writers should run out and get a bunch of different jobs. If you want to write about a brain surgeon, you can always research brain surgery in textbooks and journals or interview brain surgeons to find out about the field’s science and procedures. But what does a brain surgeon feel? What do they think when they’re messing around with someone’s most delicate organ? We need to open ourselves to our experiences, good and bad. Not only can we learn from them, but they’ll give us ways to infuse our stories and characters with emotional authenticity.

Click here if you’d like a PDF copy of the story, Handy Man, that my Tower Records experience inspired. In cyberspace, I can be found at thrillingtales.com My social media handle is @realtimchapman.

Tim Chapman’s fiction has been published in The Southeast Review, the Chicago Reader, Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Palooka, and the anthologies “The Rich and the Dead” and “Tales of the Fantastic.” His first novel, “A Trace of Gold” (originally published as “Bright and Yellow, Hard and Cold”) was a finalist in Shelf Unbound’s 2013 Best Indie Book competition. His short stories have been collected under the title “Kiddieland and other misfortunes.” His latest novel is “The Blue Silence.” When he’s not writing he’s editing the journal Litbop: Art and Literature in the Groove, teaching martial arts or painting pretty pictures.

You've had some fascinating experiences and I look forward to reading your story! Thanks for sharing! :)

It's as though you've lived 10 different lives Tim! I agree, lived experience can be worth more than a hundred hours of research. Excellent storytelling as well!